When I was asked to write this piece, my reaction was “Why me? I’m Masters, but surely not an athlete.” To me, an athlete was someone who had spent their life training, focused, competing. I came of age as Title IX was being implemented, so girls’ teams were relatively new. In my family, girls simply did not play sports beyond the occasional softball game. More than that, though, I was always told I was just not athletic. Add to that the fact that I didn’t care if I could run fast or jump high, and you get it. Not an athlete. Don’t really care. Until I started to lift. Guess what? I am an athlete. Doesn’t matter that I haven’t been lifting or playing sports for 30 years, or that I did back in the day and am back to it. I train, I study, I learn, I listen, and I compete. As a weightlifter. The lessons I’ve learned can apply to any sport.

Find a good coach who takes your interest seriously, and a training environment in which you can fail or succeed without being patronized.

There will always be someone who says, “Hey, at least ya showed up,” with a meaningful gaze and a pat on the arm. Heck with that. I prefer the teammates who whoop and holler for me when I manage to clean an extra 2 kilos, and say “Been there, that sucks” when I have a bad lifting day.

Listen to the coach. Listen to the coach. Listen to the coach. Obey.

If you think you know more than s/he does, you don’t. If you feel the need to lecture or direct or “correct” your coach, ask yourself why you are training with this person (and why they are allowing it). You are a leader in your line of work, and wouldn’t like it if a novice hired you to advise them and wouldn’t take direction. Same with the coach.

Respect your need for rest and recovery time, and don’t neglect increasing your mobility.

Working through the pain of an injury waiting to happen is different from pushing yourself. I train with fine lifters who jump up and down a few times, crack their necks, and start lifting. They will train every day if they aren’t stopped, and they can do heavy triples with a 30 second break. They are 1/3 my age. I learned quickly that I don’t do well lifting three days in a row, that I need a steady warmup and stretch. If I don’t roll out my upper back before I pick up the empty bar, I have a hard time pushing through the lift. Too much time between lifts can be just as bad as too little, but we all need to find our own rhythm.

At some point you will lift, squat or bench, more weight than someone half your age. Enjoy the moment.

If that person wants to put in the work, they’ll be kicking your butt within a month. You will work hard to maintain and harder to progress. It’s how it is.

Age is a state of mind.

It’s not something to beat people over the head with, or use as an excuse or a status tool — not to yourself, and not your teammates. I love to train with the younger athletes; their energy and love for the sport is infectious. I also love their bottom positions in the snatch, and know that I’ll never get there but as long as it doesn’t hurt, I’ll keep trying.

I am not sure I like the “I” word: Inspiration, but Masters athletes hear this a lot.

Some Masters athletes say one of their goals is to inspire others. Not me — my goal is to lift heavy weights with great form and not give myself or anyone else a concussion in the process. Just seeing middleaged me in a singlet is not a reason to be inspired, there are a lot of assumptions made with a comment like that.

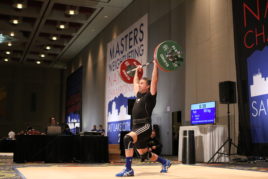

Let this inspire you: I fell in love with weightlifting when I was 57. I was (and still am) not too good at it and get distracted easily, but I stay with it. Six months after starting and one week before my first meet I couldn’t snatch an empty bar without dropping it on my head. That great feeling when I managed a 25K snatch in the meet a few days later will be something I remember forever. And with that in mind, I’m going to be a lifter until I go to that big platform in the sky.